from Parfit Derek’s book: “Reasons and Persons”

36. How Common-Sense Morality Is Directly Self-Defeating

As I implied in Section 22, the Self-interest Theory is not the only theory that can produce Each-We Dilemmas. Such cases may occur when:

(a) some theory T is agent-relative, giving to different agents different aims,

(b) the achievement of each person’s T-given aims partly depends on what others do

(c) what each does will not affect what these others do

These conditions often hold for Common-Sense Morality.

Most of us believe that there are certain people to whom we have special obligations. These are the people to whom we stand in certain relations—such as our children, parents, friends, benefactors, pupils, patients, clients, colleagues, members of our own trade union, those whom we represent, or our fellow-citizens. We believe that we ought to try to save these people from certain kinds of harm, and ought to try to give them certain kinds of benefit. Common-Sense Morality largely consists in such obligations.

Carrying out these obligations has priority over helping strangers. This priority is not absolute. I ought not to save my child from a cut or bruise rather than saving a stranger’s life. But I ought to save my child from some harm rather than saving a stranger from a somewhat greater harm. My duty to my child is not overridden whenever I could do somewhat greater good elsewhere.

When I try to protect my child, what should my aim be? Should it simply be that he is not harmed? Or should it rather be that he is saved from harm by me? If you would have a better chance of saving him from harm, I would be wrong to insist that the attempt be made by me. This shows that my aim should take the simpler form. We can face Parent’s Dilemmas. Consider:

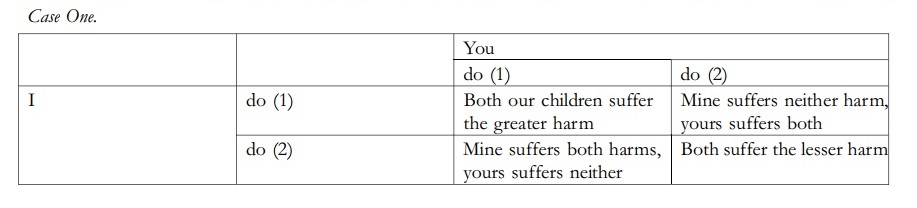

Case One. We cannot communicate. But each could either (1) save his own child from some harm or (2) save the other’s child from another somewhat greater harm. The outcomes are shown below.

Since we cannot communicate, neither’s choice will affect the other’s. If the aim of each should be that his child not be harmed, each should here do (1) rather than (2). Each would thus ensure that his child is harmed less. This is so whatever the other does. But if both do (1) rather than (2) both our children will be harmed more.

Consider next those benefits that I ought to try to give my child. What should my aim here be? Should I insist that it be I who benefits my child, even if this would be worse for him? Some would always answer No. But this answer may be too sweeping. It treats parental care as a mere means. We may think it more than that. We may agree that, with some kinds of benefit, my aim should take the simpler form. It should simply be that the outcome be better for my child. But there may be other kinds of benefit that my child should receive from me. With both kinds of benefit, we can face Parent’s Dilemmas. Consider:

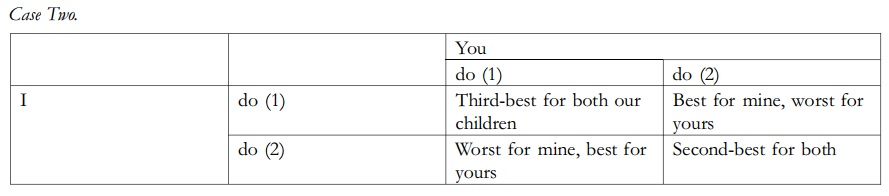

Case Two. We cannot communicate. But each could either (1) benefit his own child or (2) benefit the other’s child somewhat more. The outcomes are shown below.

If my aim should here be that the outcome be better for my child, I should again do (1) rather than (2). And the same holds for you. But if both do (1) rather than (2) this will be worse for both our children. Compare:

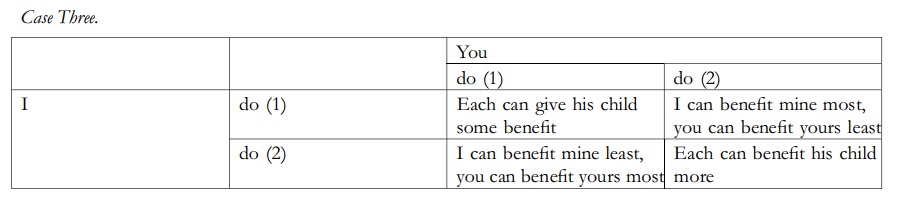

Case Three. We cannot communicate. But I could either (1) enable myself to give my child some benefit or (2) enable you to benefit yours somewhat more. You have the same alternatives with respect to me. The outcomes are shown below.

If my aim should here be that I benefit my child, I should again do (1) rather than (2). And the same holds for you. But if both do (1) rather than (2) each can benefit his child less. Note the difference between these two examples. In Case Two we are concerned with what happens. The aim of each is that the outcome be better for his child. This is an aim that the other can directly cause to be achieved. In Case Three we are concerned with what we do. Since my aim is that I benefit my child, you cannot, on my behalf, do so. But you can help me to do so. You can thus indirectly help my aim to be achieved.

Two-Person Parent’s Dilemmas are unlikely to occur. But we often face Many-Person Versions. It is often true that, if all rather than none give priority to our own children, this will either be worse for all our children, or will enable each to benefit his own children less. Thus there are many public goods: outcomes that would benefit our children whether or not we help to produce them. It can be true of each parent that, if he does not help, this will be better for his own children. What he saves—whether in money, time, or energy—he can spend to benefit only his own children. But, if no parent helps to produce this public good, this will be worse for all our children than if all do. In another common case, such as the Fisherman’s Dilemma, each could either (1) add to his own earnings or (2) (by self-restraint) add more to the earnings of others. It will here be true of each that, if he does (1) rather than (2), he can benefit his children more. This is so whatever others do. But if all do (1) rather than (2) each can benefit his children less. These are only two of the ways in which such cases can occur. There are many others.

Similar remarks apply to all similar obligations—such as those to pupils, patients, clients, or constituents. With all such obligations, there are countless many-person versions like my three Parent’s Dilemmas. They are as common, and as varied, as Many-Person Prisoner’s Dilemmas. As we have just seen, they will often have the same cause.

Here is another way in which this might be true. Suppose that, in the original Prisoner’s Dilemma, it is our lawyers who must choose. This yields the Prisoner’s Lawyer’s Dilemma. If both lawyers give priority to their own clients this will be worse for both clients than if neither does. Any self-interested Dilemma may thus yield a moral Dilemma. If one group face the former, another may in consequence face the latter. This may be so if each member of the second group ought to give priority to some members of the first. A similar claim applies when different groups, such as nations, face a self-interested Dilemma. Most governments believe that they ought to give priority to the interests of their citizens. There are several ways in which, if all governments rather than none give priority to their own citizens, this will be worse for all their citizens. The problem comes from the giving of priority. It makes no difference whether this is given to oneself or others. My examples all involve harms or benefits. But the problem can arise for other parts of Common-Sense Morality. It can arise whenever this morality gives to different people different duties. Suppose that each could either (1) carry out some of his own duties or (2) enable others to carry out more of theirs. If all rather than none give priority to their own duties, each may be able to carry out fewer. Deontologists can face Each-We Dilemmas.

<end of Chapter 36>

Be the first to comment on "36. How Common-Sense Morality Is Directly Self-Defeating – Derek Parfit"